Rows: 32

Columns: 10

$ sample_name <chr> "OXFT_209", "OXFT_1769", "OXFT_2093", "OXFT_1770", "OXFT_1…

$ filename <chr> "gsm65344.cel.gz", "gsm65345.cel.gz", "gsm65347.cel.gz", "…

$ treatment <chr> "tamoxifen", "tamoxifen", "tamoxifen", "tamoxifen", "tamox…

$ er <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1…

$ grade <dbl> 3, 1, 1, 1, 3, 3, 1, 3, 1, 3, 3, 1, 3, 1, 1, 1, 1, 3, 1, 3…

$ node <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0…

$ size <dbl> 2.5, 3.5, 2.2, 1.7, 2.5, 1.4, 3.3, 2.4, 1.7, 3.5, 1.4, 2.0…

$ age <dbl> 66, 86, 74, 69, 62, 63, 76, 61, 62, 65, 63, 70, 78, 71, 68…

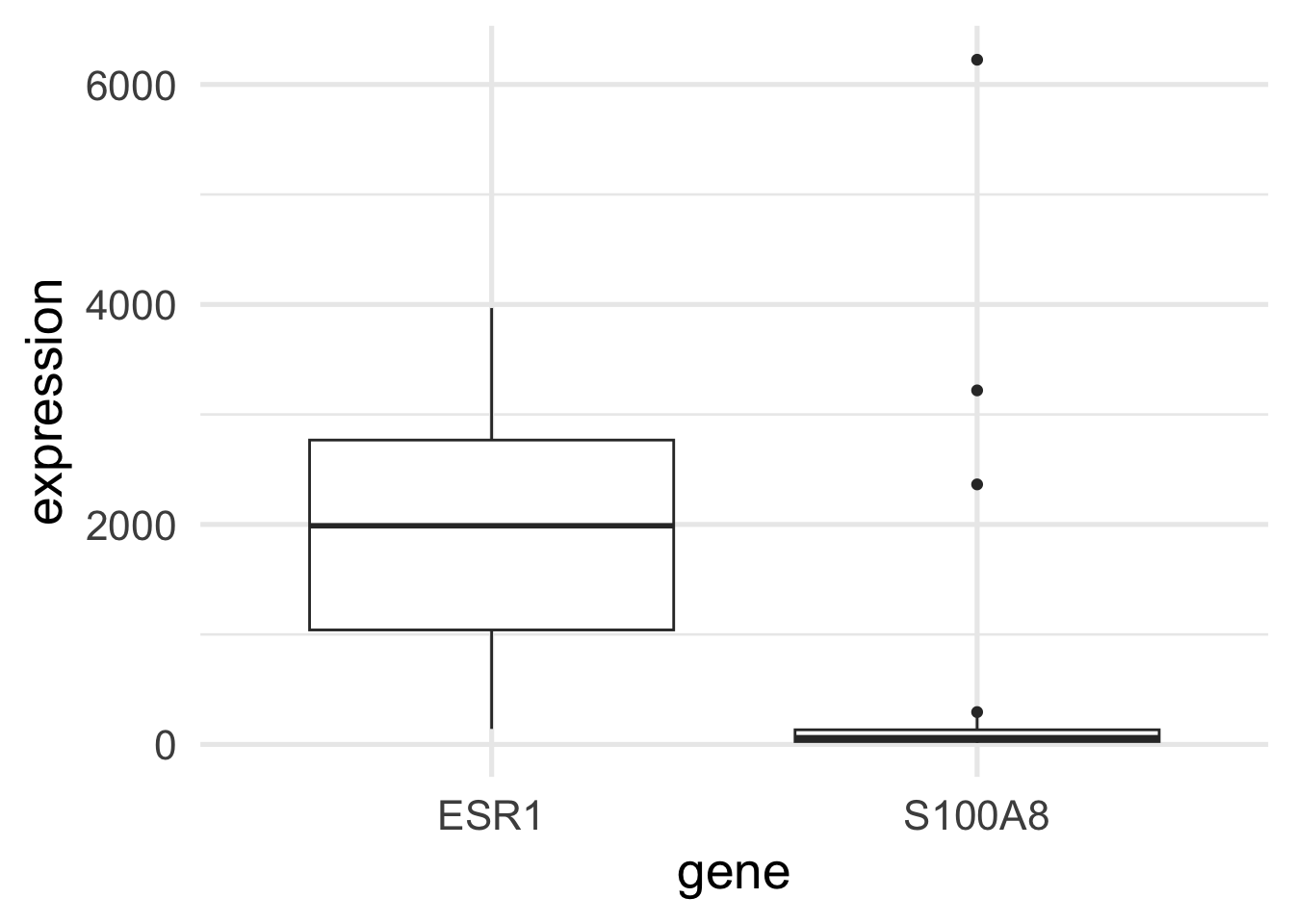

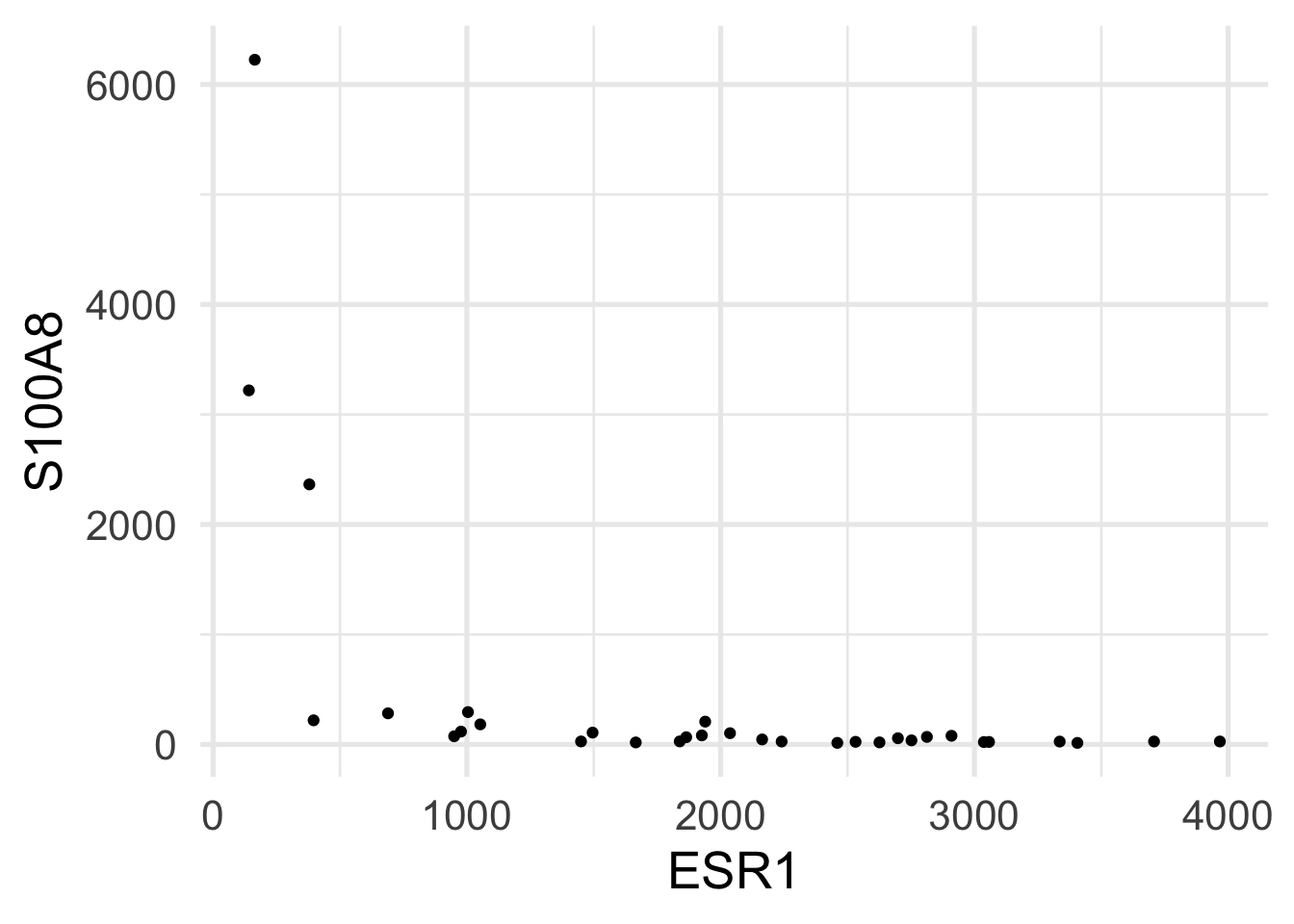

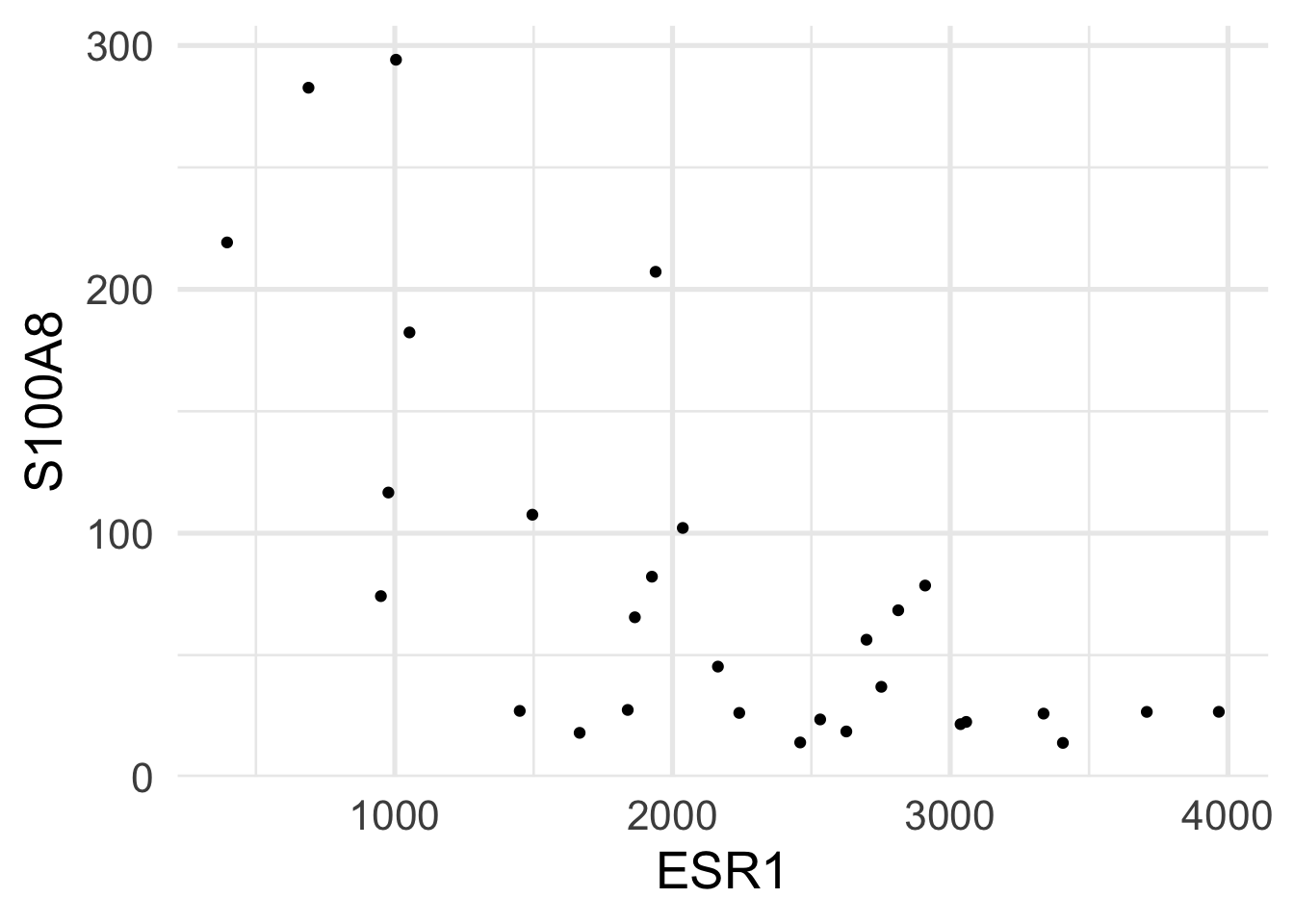

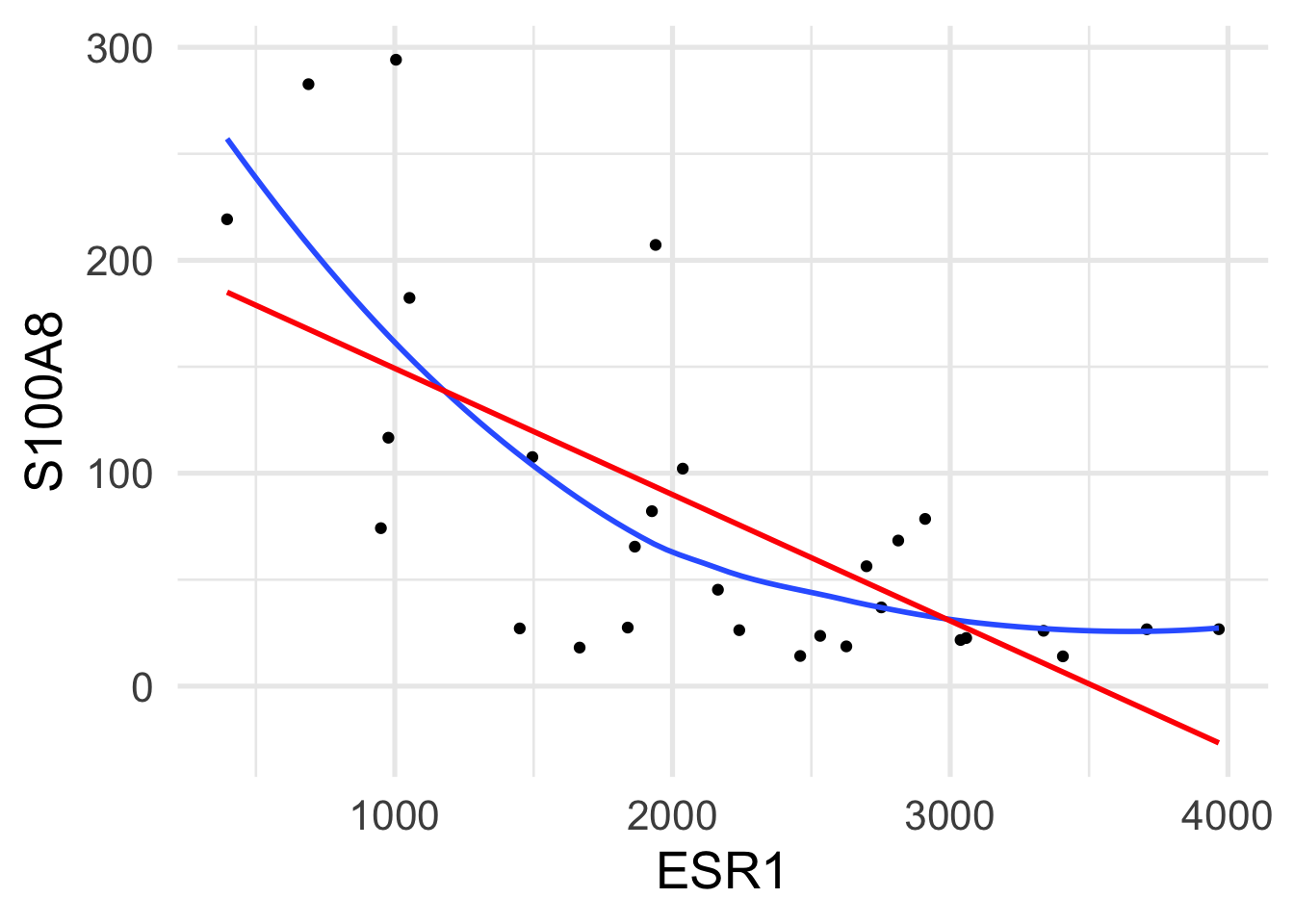

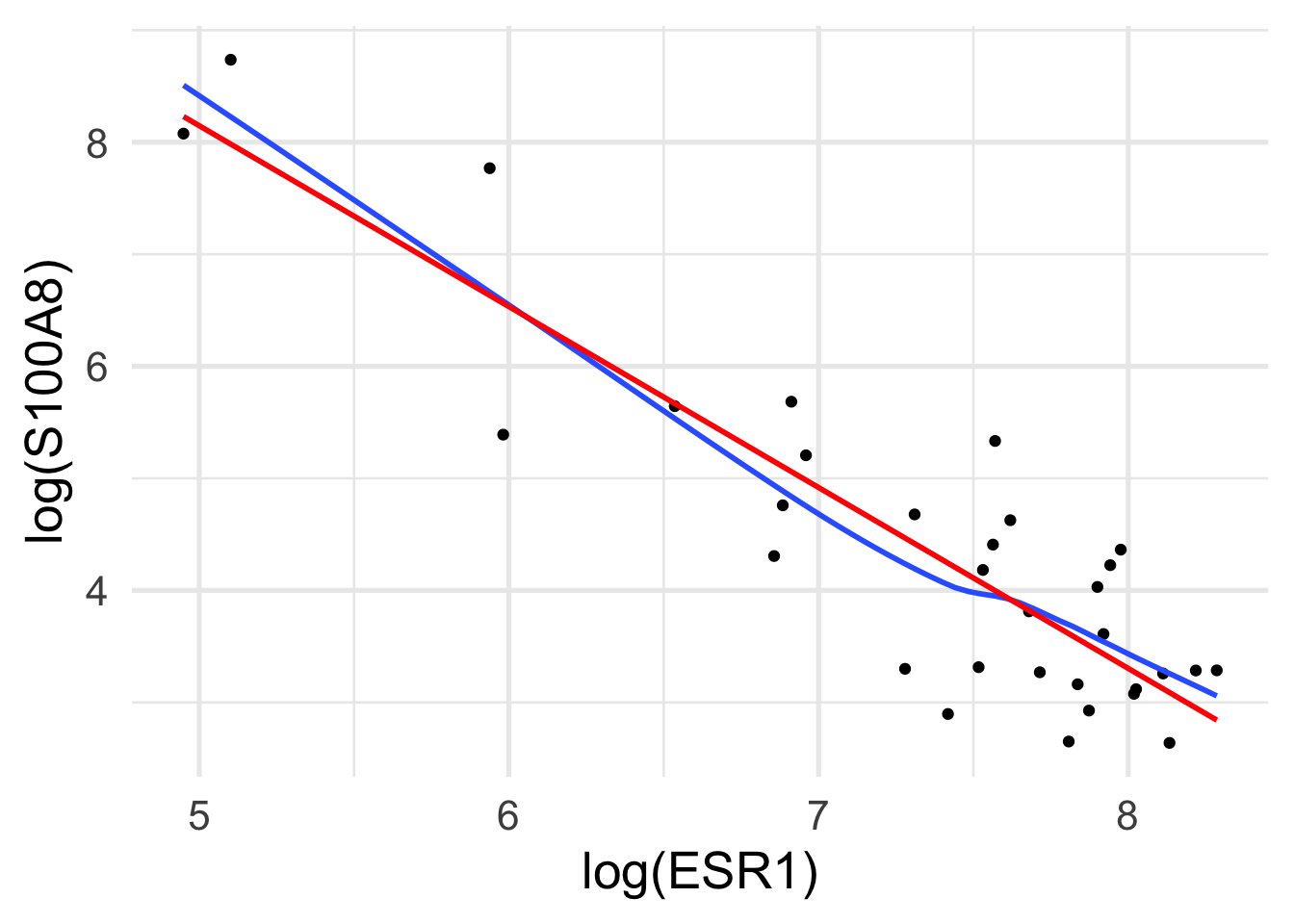

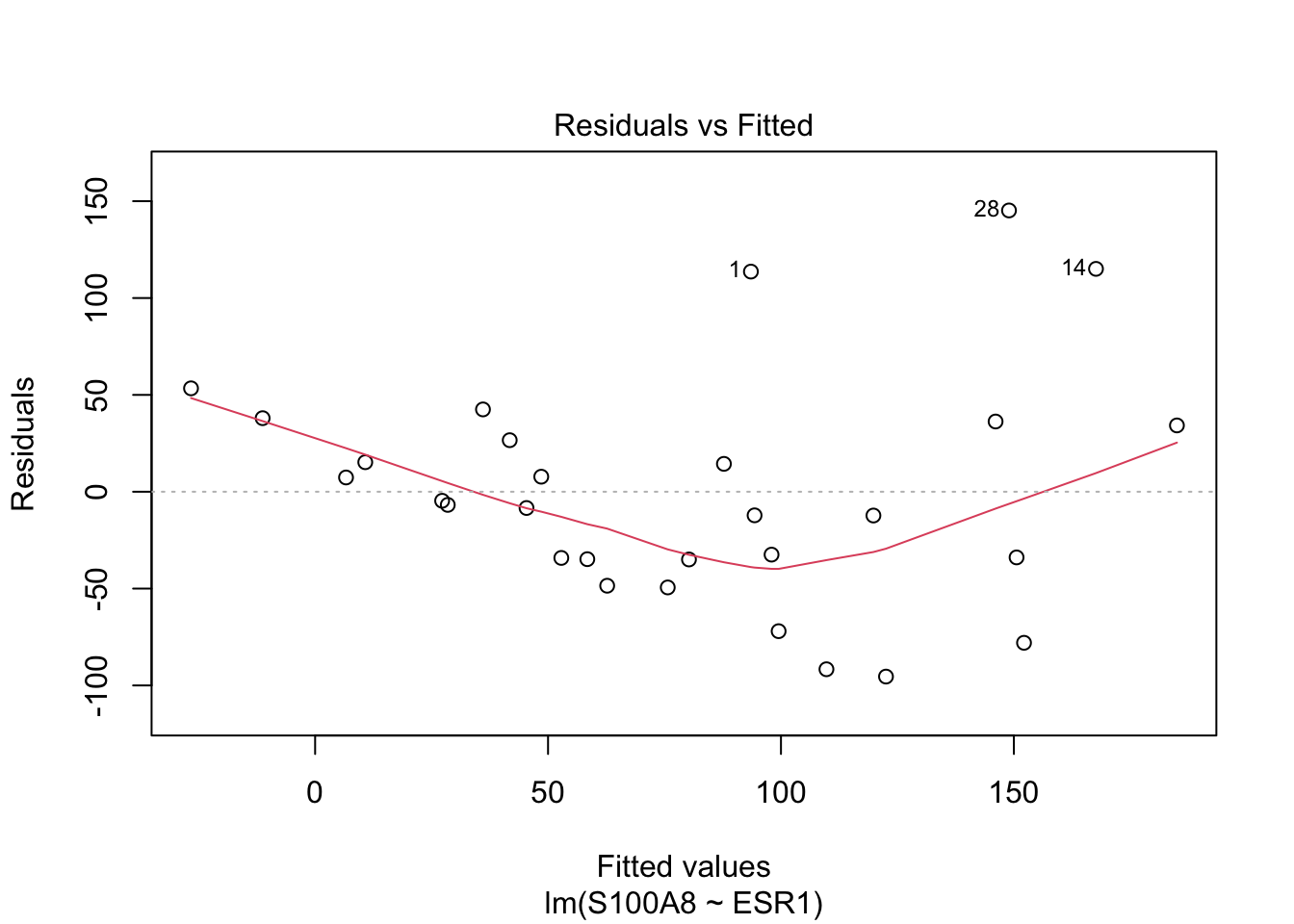

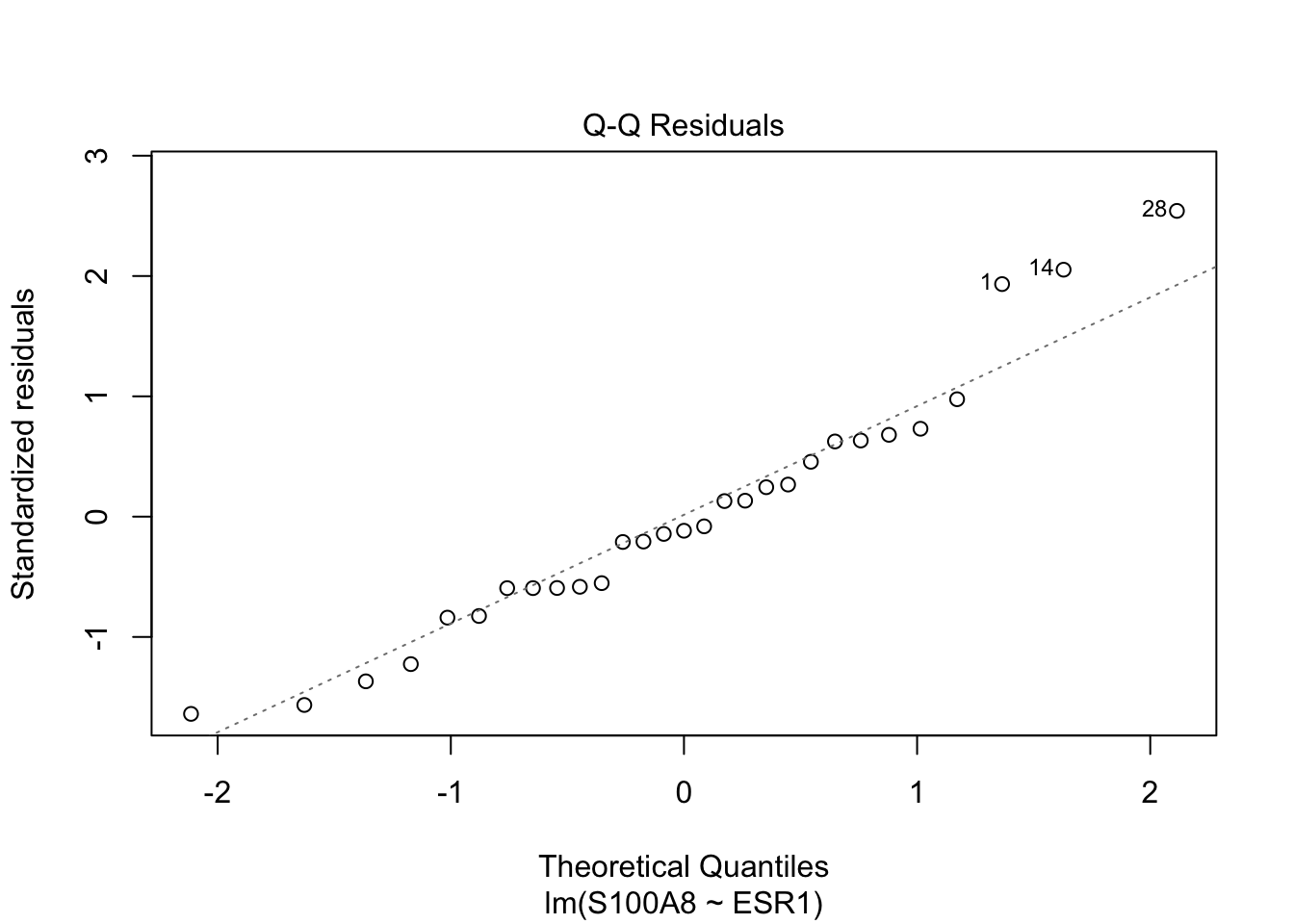

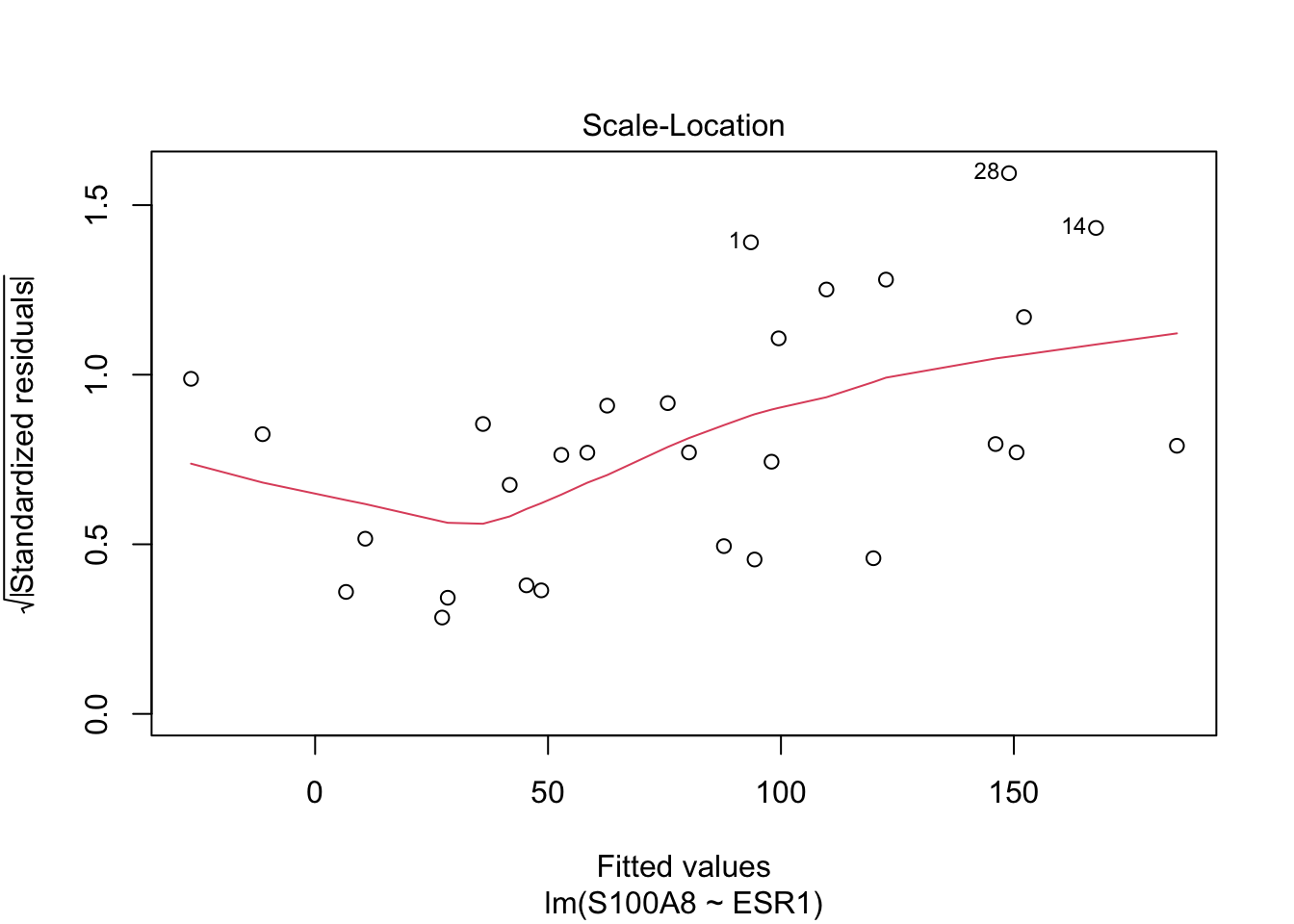

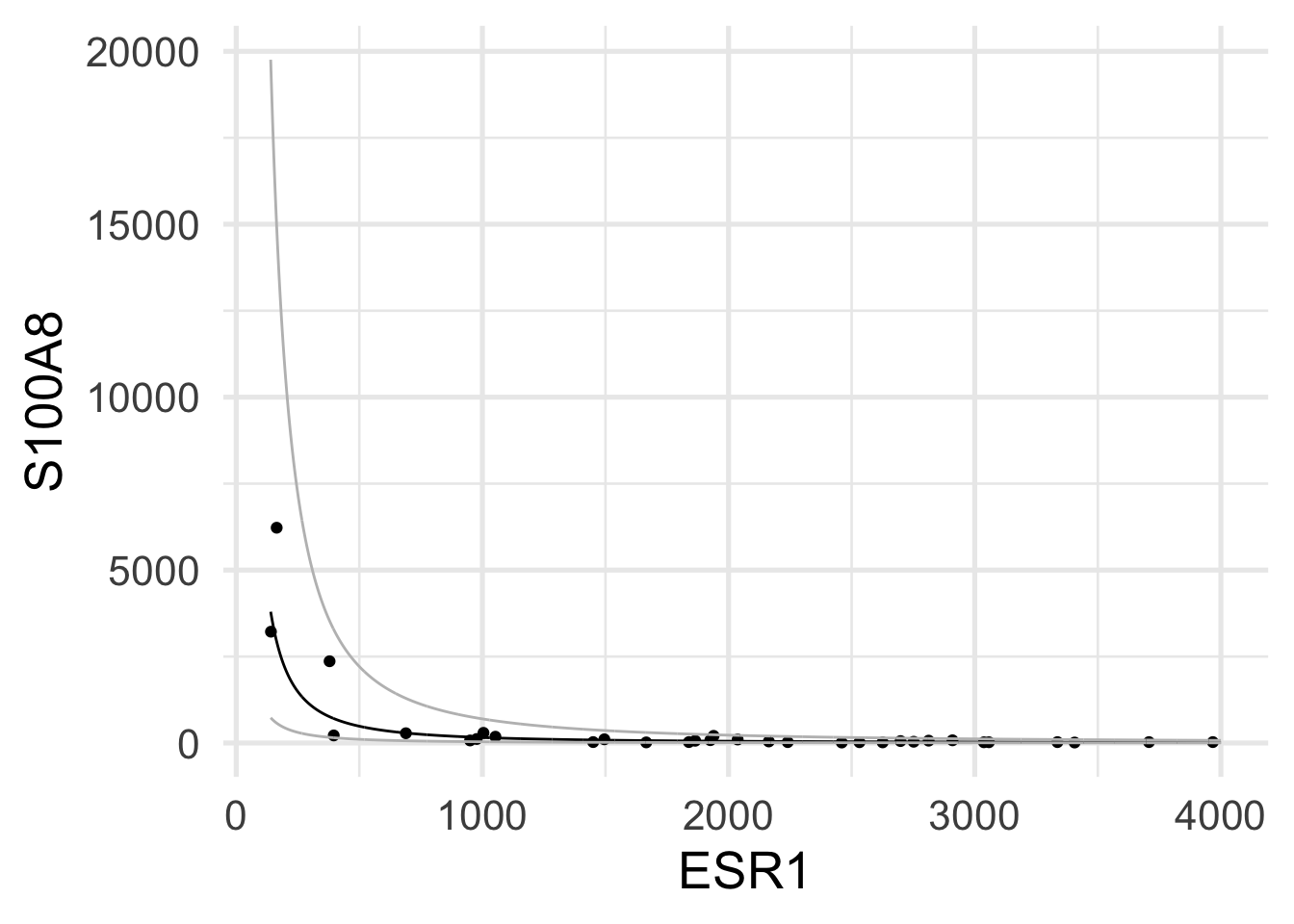

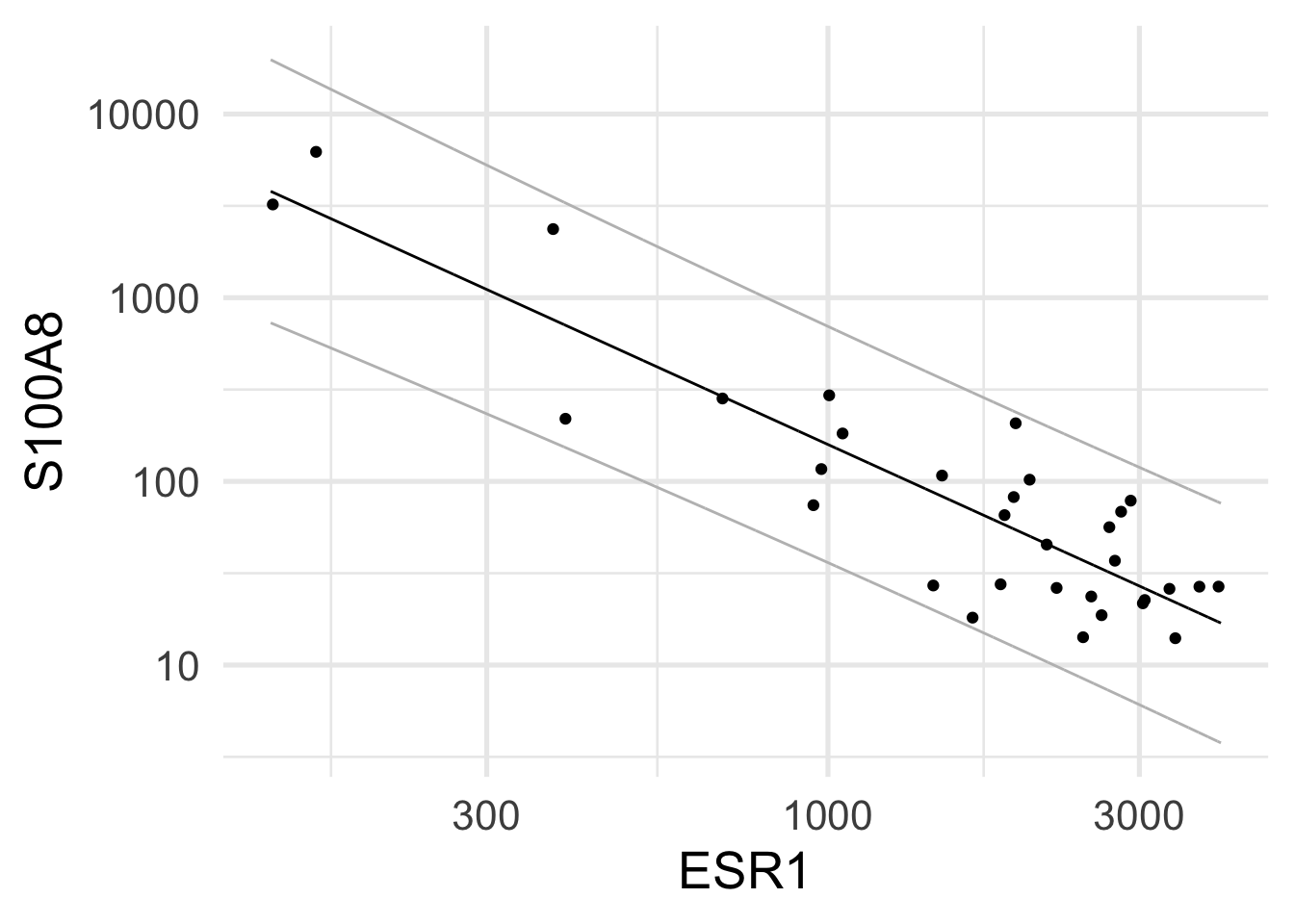

$ ESR1 <dbl> 1939.1990, 2751.9521, 379.1951, 2531.7473, 141.0508, 1495.…

$ S100A8 <dbl> 207.19682, 36.98611, 2364.18306, 23.61504, 3218.74109, 107…