Generalized Linear Models

Advanced Statistics and Data Analysis

Introduction

Linear models

Linear models are the most useful applied statistics technique.

However, they have their limitations:

- The response may not be continuous

- The response may have a limited range of possible values

In such cases, linear models are not ideal and we may want to consider generalizations of it.

Generalized Linear Models (GLMs)

The Generalized Linear Model (GLM) is a family of models that includes the linear model and extend it to situations in which the response variable has a distribution of the exponential family.

The exponential family is a family of distributions that includes the Gaussian, Poisson, Binomial, Gamma, among others.

Exponential Family

The density function of a distribution of the exponential family can be written as \[ f(y_i; \theta_i, \phi) = \exp \left\{\frac{y_i \theta_i - b(\theta_i)}{a(\phi)} + c(y_i, \phi)\right\}, \] where:

- \(\theta_i\) are the canonical parameters;

- \(\phi\) is the dispersion parameter;

- \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\) are functions that depend on the specific distribution.

Example: Poisson distribution

The probability function of a Poisson distribution can be written as \[ f(y_i; \lambda_i) = \frac{\lambda_i^{y_i} e^{-\lambda_i}}{y_i!}, \]

or equivalently as \[ f(y_i; \lambda_i) = \exp\left\{y_i \log(\lambda_i) - \lambda_i - \log(y_i!)\right\}, \]

which corresponds to an exponential family with:

- \(\theta_i = \log(\lambda_i)\);

- \(b(\theta_i) = \exp(\theta_i)\);

- \(a(\phi) = 1\);

- \(c(y_i, \phi) = -\log(y_i!)\).

Log-likelihood function

Note that the log-likelihood function of the exponential family can be written as \[ \ell(\lambda; y) = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{y_i \theta_i - b(\theta_i)}{a(\phi)} + c(y_i, \phi). \]

One can show that: \[ E[Y_i] = \mu_i = b'(\theta_i) \] and \[ Var(Y_i) = b''(\theta_i) a(\phi), \]

where \(b'()\) and \(b''()\) are the first and second derivative of \(b\).

Important

Note that the variance depends on the mean!

Example: Poisson distribution

In the case of the Poisson, \(b(\theta_i) = \exp(\theta_i)\) and \(a(\phi) = 1\), hence:

\[ E[Y_i] = \exp(\theta_i) = \lambda_i \] and

\[ Var(Y_i) = \exp(\theta_i) = \lambda_i. \]

Generalizations of the linear model

We can think of GLMs as a two-way generalization of linear models:

We can use a function of the linear predictor to transform it to a range of values that is more useful for the application.

We can use a different distribution for the error terms other than the Gaussian.

Likelihood estimation

Recall that ordinary least squares can be seen as the maximum likelihood estimate of the linear regression parameters.

The idea is that by changing the distribution of the response variable, we can still use maximum likelihood to estimate the regression coefficients, but specifying a different likelihood function.

The three components of a GLM

The three components that we need in order to fully specify a GLM are:

An exponential family distribution for the response.

A link function that connects the linear predictor to the response.

A variance function that specifies how the variance depends on the mean.

Example: the normal linear model

If we assume that:

The response variable is distributed as a Gaussian r.v.

The link function is the identity function.

The variance is constant with respect to the mean.

Then, we have the standard linear model.

Example: the normal linear model

In formulas:

\(Y \sim \mathcal{N}( \mu, \sigma^2)\).

\(E[Y | X] = X \beta\).

\(V(\mu) = \sigma^2\).

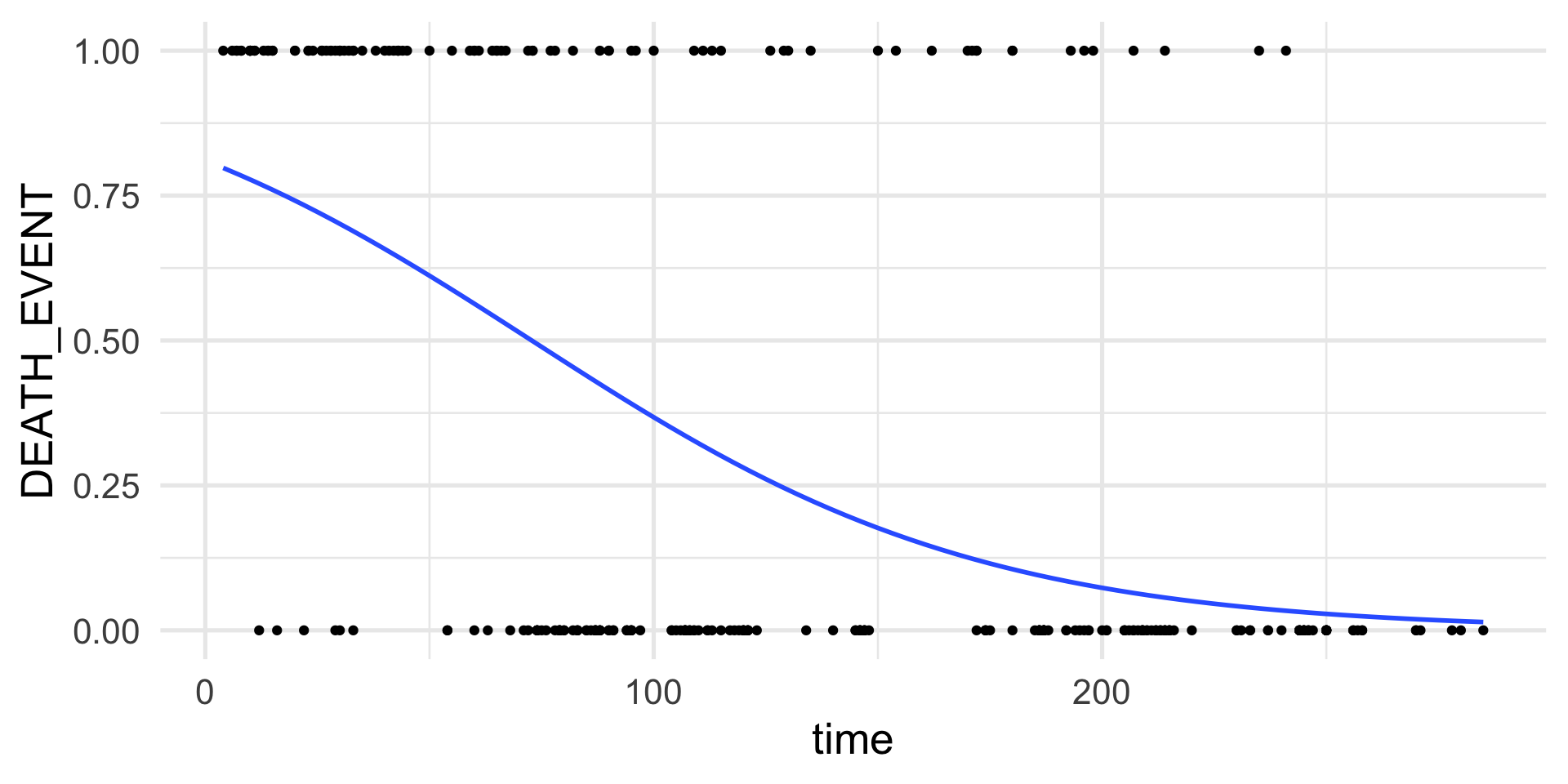

Example: logistic regression

Logistic regression assumes that:

The response variable is distributed as a Bernoulli r.v.

The link function is the logistic function.

The variance is a function of the mean.

Example: logistic regression

In formulas:

\(Y \sim \mathcal{Be}(\mu)\).

\(g(E[Y | X]) = X \beta\), where \(g(\mu) = \log \left(\frac{\mu}{1-\mu}\right)\).

\(V(\mu) = \mu (1 - \mu)\).

Note that the link function implies that \[ \mu = \frac{\exp(X \beta)}{1 + \exp(X\beta)}. \]

Example: logistic regression

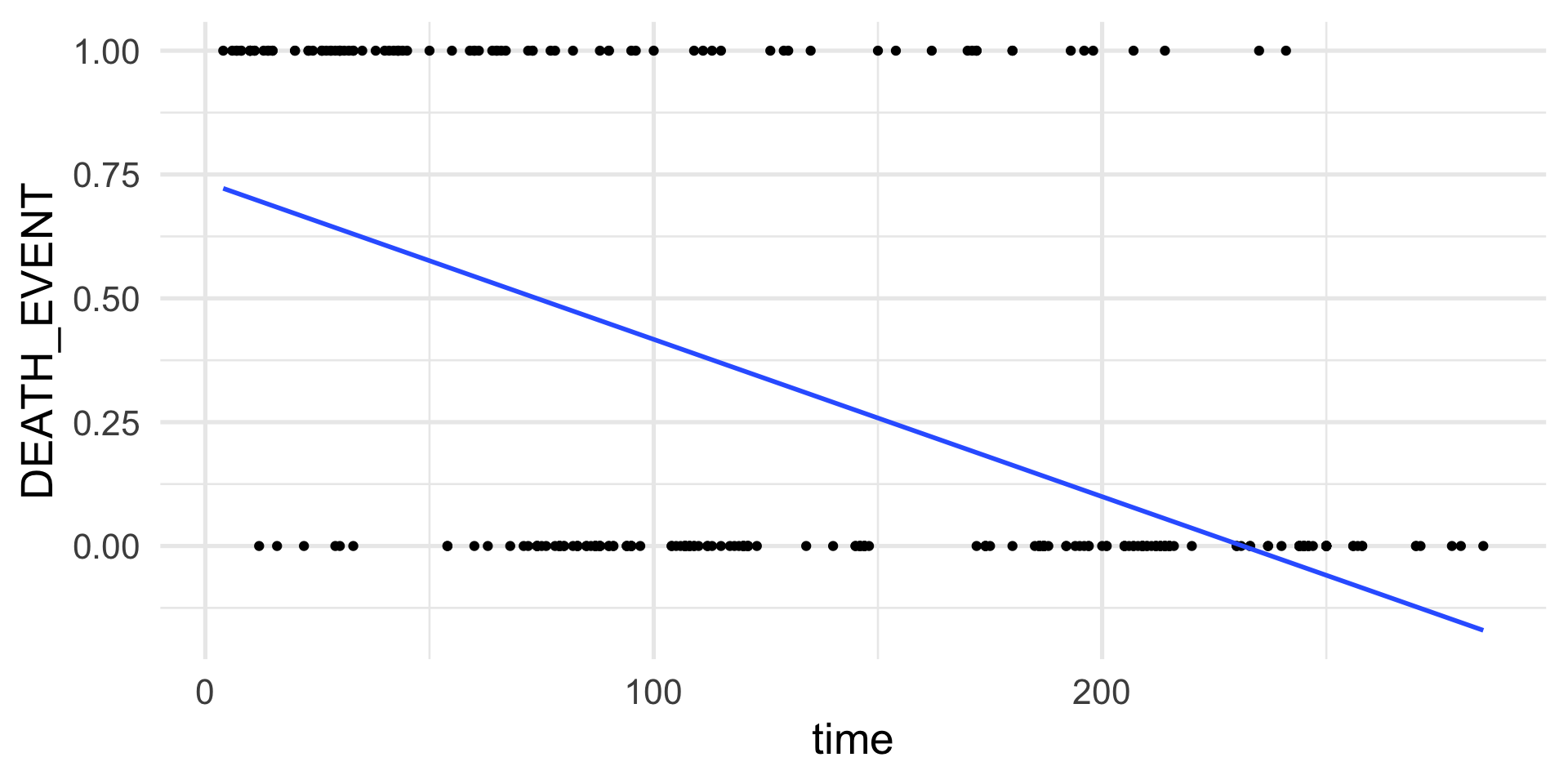

Assume that we have collected data from 299 patients that had heart failure.

For each patient we measure if they died or survived after a follow-up period.

We can use a set of 13 clinical features to try to predict patient survival.

- In total, 96 patients out of 299 died.

Example: logistic regression

Example: logistic regression

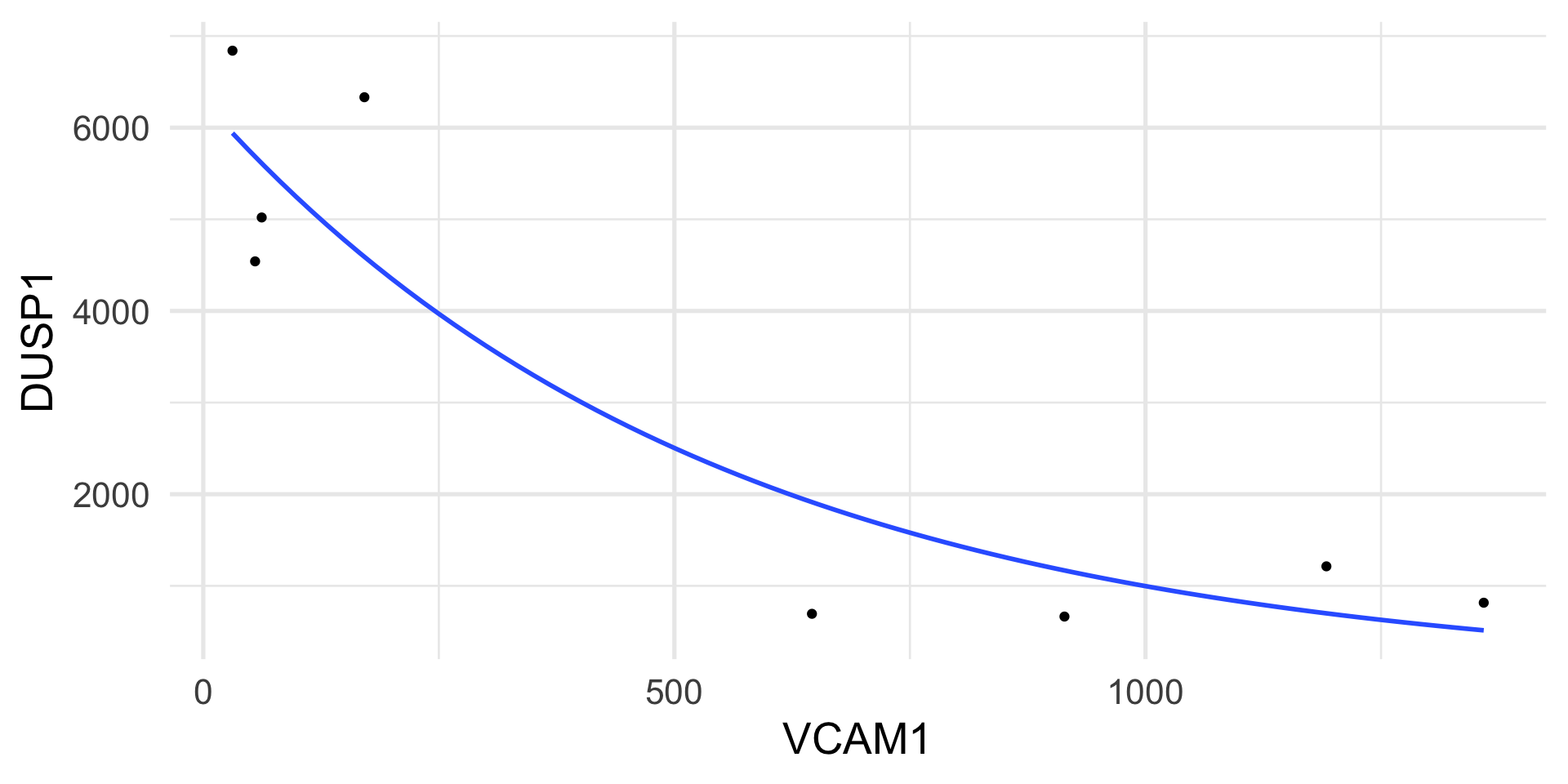

Example: Poisson regression

Poisson regression (or log-linear regression) assumes that:

The response variable is distributed as a Poisson r.v.

The link function is the log function.

The variance is a function of the mean.

Example: Poisson regression

In formulas:

\(Y \sim \mathcal{Poi}(\mu)\).

\(g(E[Y | X]) = X \beta\), where \(g(\mu) = \log(\mu)\).

\(V(\mu) = \mu\).

Note that the link function implies that \[ \mu = \exp(X \beta) \]

The log is called the canonical link function because it is equal to the function that transforms the mean into the canonical parameter in the exponential family formulation.

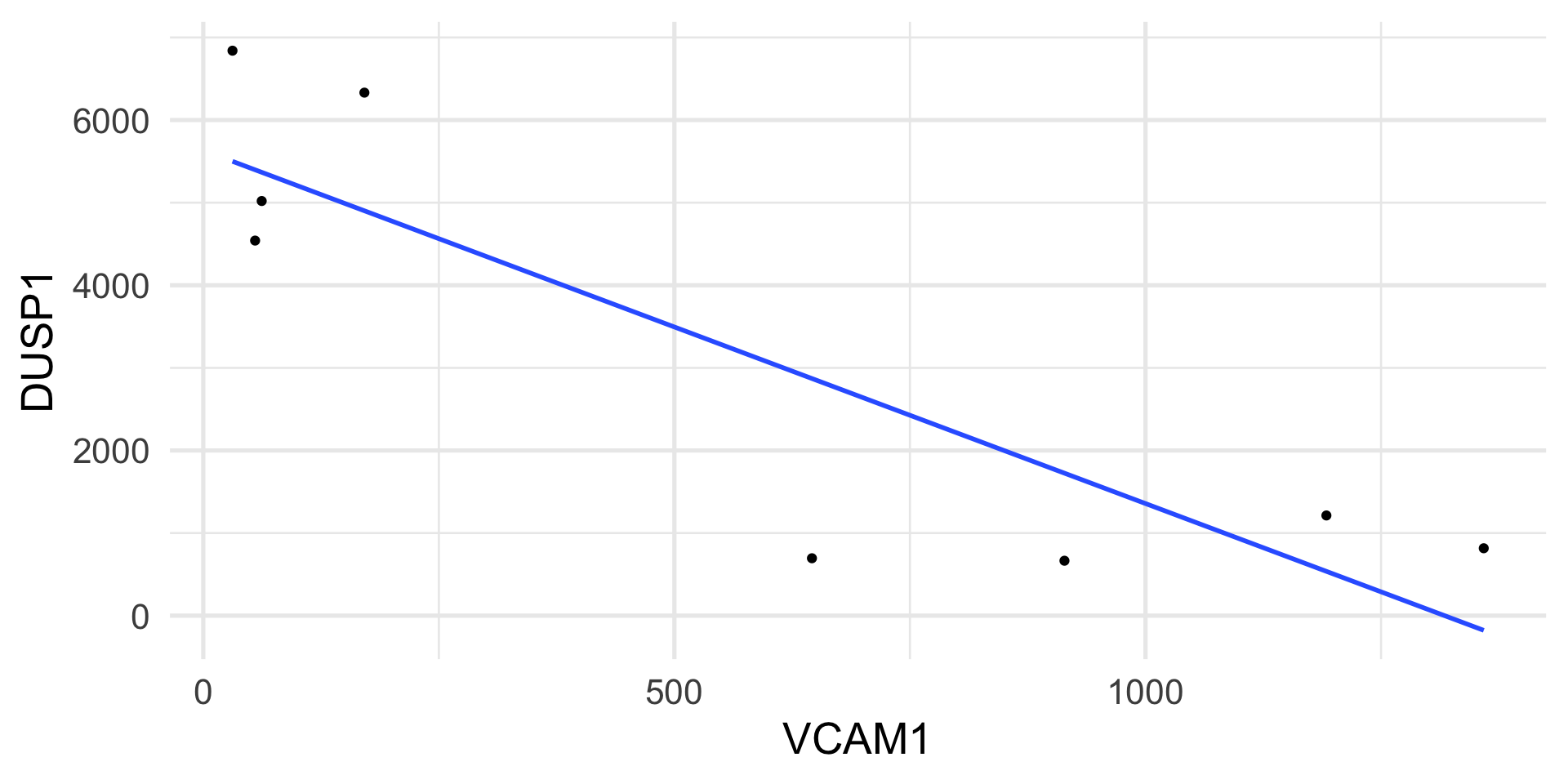

Example: Poisson regression

We measure the expression of two genes, DUSP1 and VCAM1, in airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell lines.

The DUSP1 gene plays an important role in the human cellular response to environmental stress.

The VCAM1 gene is involved in cell adhesion and signal transduction.

The genes are measured with an assay that yields counts as a measure of gene expression.

Example: Poisson regression

Example: Poisson regression

Parameter estimation

Log-likelihood of a GLM

In principle, we can maximize the log-likelihood as a function of the regression coefficients.

In fact, once we have defined a relationship between the parameter of the model and the predictors, we can write the likelihood as a function of \(\beta\).

In the case of the Poisson, the log-likelihood is \[ \ell(\beta; X, y) = \sum_{i=1}^n y_i \eta_i- \exp\{\eta_i\}, \] where \(\eta_i = \log(\mu_i) = \sum_{k=1}^p x_{ik} \beta_k\).

Score function

The derivative of the log-likelihood with respect to \(\theta\) is also called the score function.

One can show that in the exponential family, the score function \[ S(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{y_i - \mu_i}{a(\phi)}, \]

when you want to derive for \(\beta\), the chain rule of differentiation gives \[ S(\beta) = \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{Y_i - \mu_i}{Var(Y_i)} \frac{d \mu_i}{d \eta_i} X^\top = X^\top A (Y - \mu), \]

where \(A\) is a diagonal matrix with elements \(a_{ii} = (Var(Y_i) \frac{d \eta_i}{d \mu_i})^{-1}\).

Important

Note the relation with least squares!

Poisson example

In Poisson data:

- \(Var(Y_i) = E[Y_i] = \mu_i\);

- \(\eta_i = \log(\mu_i)\), hence \(\frac{d \eta_i}{d \mu_i} = \frac{1}{\mu_i}\).

Hence, \(A = I\), the identity matrix and \[ S(\beta) = X^\top (Y - \mu). \]

Solving the score equations

To find the MLE we need to solve the equation \[ S(\beta) = X^\top A (Y - \mu) = 0. \]

The problem is that this is non linear in \(\beta\) because of the link function.

We hence need numerical algorithms to find the values of \(\beta\) that solve this equation.

Newton-Raphson

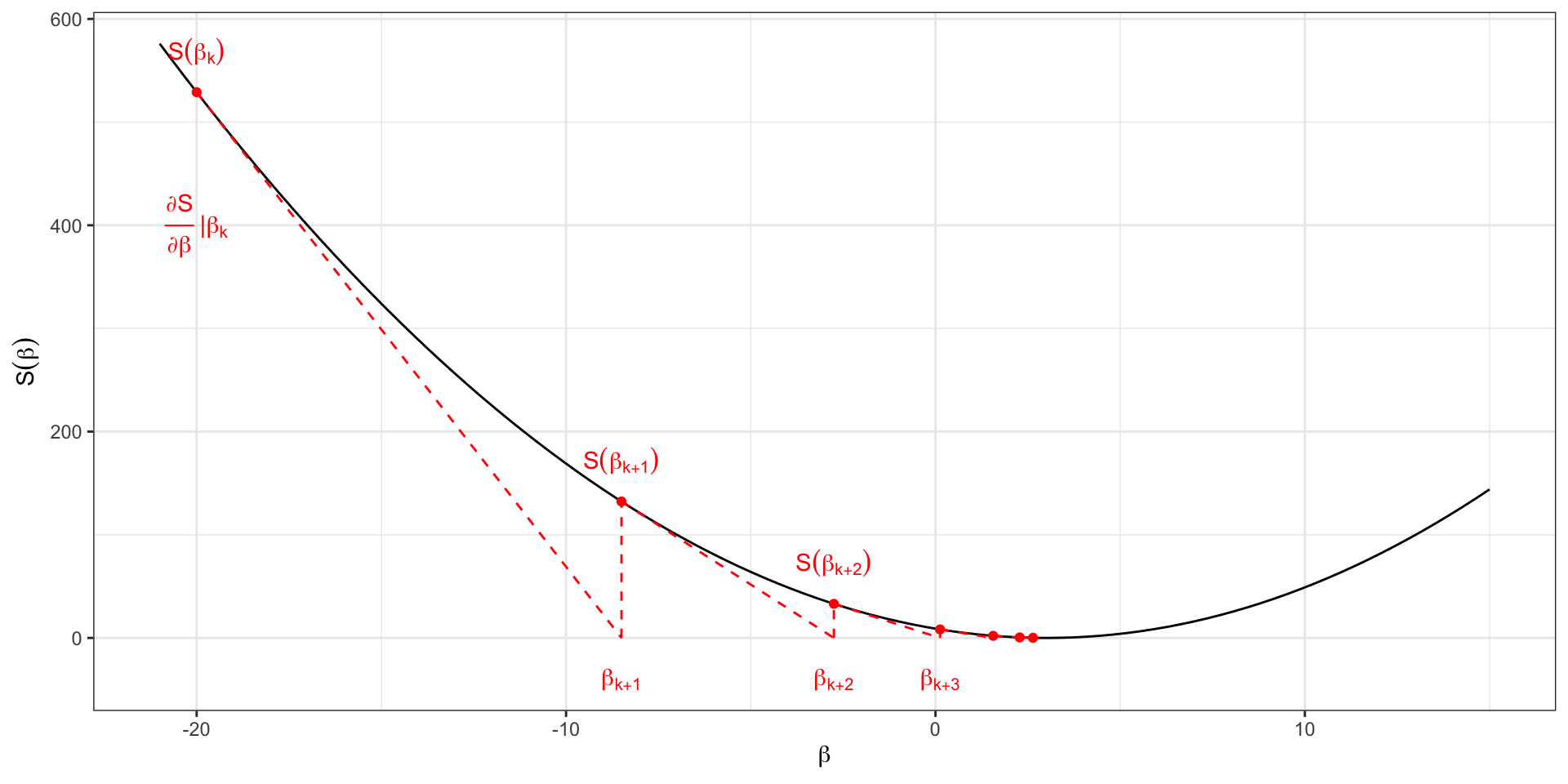

Newton-Raphson

The Newton-Raphson algorithm is a numerical algorithm to find the “root” of a function, i.e., to find the value for which that function is equal to 0.

It starts from an initial guess, say \(\beta_k\), and moves in the direction of the derivative until it intersects the zero line.

Newton-Raphson

Specifically:

- Choose an initial parameter estimate \(\beta_k\);

- Calculate the score \(S(\beta_k)\);

- Calculate the derivative \(\frac{\partial S(\beta)}{\partial \beta}\) at the value \(\beta_k\);

- Go in the direction of the derivative until the point, \(\beta_{k+1}\) in which it crosses the zero line;

- Update the value of \(\beta\) to \(\beta_{k+1}\);

- Iterate 2-5 until convergence.

Derivative of the score

For the Newton-Raphson algorithm to work, we need to compute the derivative of the score function.

One can show that it is \[ \frac{\partial S(\beta)}{\partial \beta} = - X^\top W X, \] where \(W\) is a diagonal matrix with elements \[ w_{ii} = \frac{(d \mu_i / d \eta_i)^2}{Var(Y_i)} \]

Iteratively Reweighted Least Squares

Now that we know the derivative, we can rewrite the Newton-Raphson algorithm as the Iteratively Reweighted Least Squares (IRLS).

In fact we can show that \[ \beta_{k+1} = \beta_k + (X^\top W X)^{-1} S(\beta_k) \] or equivalently \[ \beta_{k+1} = (X^\top W X)^{-1} X^\top W Z, \] where \[ Z = X \beta_k + \frac{\partial \eta}{\partial \mu} (Y - \mu). \]

Interpretation of IRLS

Note that the estimate of \(\beta\) at iteration \(k\) is similar to the least squares estimator, but it is weighted by a function of the variance.

This is a way to account for the heteroschedasticity of the data.

In R: the glm() function

In R there is a very convenient function that implements the IRLS algorithm and has a syntax very similar to the lm() function.

In addition to the formula, you need to specify the family of distributions you want to specify for the response variable and (implicitly or explicitly) the link function.

Example: Poisson regression

In the airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell lines, we have two additional variables to consider:

The cell lines were either untreated or treated with dexamethasone (

dex).The cell lines were derived from four distinct donors (

cell).

It is of interest to check whether the DUSP1 gene changes between treated and control cells, potentially accounting for the differences in cell lines.

Example: Poisson regression

Call: glm(formula = DUSP1 ~ dex, family = poisson, data = df)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) dextrt

6.742 1.903

Degrees of Freedom: 7 Total (i.e. Null); 6 Residual

Null Deviance: 16880

Residual Deviance: 831.4 AIC: 911.5Interpretation of the parameters

The Poisson regression model can be written as \[ \log \mu_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i}, \] where \(x_i=1\) if the cells are treated and \(x_i=0\) if untreated.

Hence, \[ \log(\mu_i | x_i = 1) - \log(\mu_i | x_i = 0) = \beta_1 \]

which leads to \[ \beta_1 = \log \left(\frac{\mu_i | x_i = 1}{\mu_i | x_i = 0}\right). \]

Example: logistic regression

In the heart failure dataset, we may be interested in the relation between diabetes and heart failure.

Example: logistic regression

Call: glm(formula = DEATH_EVENT ~ diabetes, family = binomial, data = heart)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) diabetes

-0.745333 -0.008439

Degrees of Freedom: 298 Total (i.e. Null); 297 Residual

Null Deviance: 375.3

Residual Deviance: 375.3 AIC: 379.3Interpretation of the parameters

The logistic regression model can be written as \[ \log \left( \frac{\mu_i}{1-\mu_i} \right)= \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i}, \] where \(x_i=1\) if the subject has diabetes and \(x_i=0\) if not.

Hence, \[ \log \left( \frac{\mu_1}{1-\mu_1} \right) - \log \left( \frac{\mu_0}{1-\mu_0} \right) = \beta_1, \] where we indicate with \(\mu_1 = E[Y|x=1]\) and \(\mu_0 = E[Y|x=0]\).

We can thus interpret \(\beta_1\) as the log odds ratio \[ \beta_1 = \log OR = \log \left(\frac{\mu_1 / (1-\mu_1)}{\mu_0 / (1-\mu_0)}\right). \]

Inference

Likelihood Ratio Test

The analogous of the sum of squares and the F test in GLMs is the log-likelihood and the likelihood ratio test.

We can use the likelihood to compare two models, as we have done with the F statistics in linear models.

One can show that, when \(n \to \infty\), \[ D = 2 [\ell(\hat\beta) - \ell(\hat\beta^0)] \stackrel{H_0}{\sim} \chi^2_{df-df_0}, \]

where \(\hat\beta\) and \(\hat\beta^0\) are the estimates of the coefficient under the full and reduced model, with \(df\) and \(df_0\) degrees of freedom, respectively.

Wald Test

An alternative to the LRT is the Wald test, that leverages the fact that when \(n \to \infty\), \[ \hat\beta \stackrel{H_0}{\sim} \mathcal{N}(\beta, (X^\top W X)^{-1}). \]

Hence, the statistic \[ t = \frac{\hat\beta_k}{\sqrt{[(X^\top W X)^{-1}]_{kk}}} \stackrel{H_0}{\sim} N(0, 1) \] can be used to compute confidence intervals and test the null hypothesis \(\beta_k = 0\).

Example: Poisson regression

In the airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell lines, we have two additional variables to consider:

The cell lines were either untreated or treated with dexamethasone (

dex).The cell lines were derived from four distinct donors (

cell).

It is of interest to check whether the DUSP1 gene changes between treated and control cells, potentially accounting for the differences in cell lines.

Poisson regression: Wald test

Call:

glm(formula = DUSP1 ~ dex, family = poisson, data = df)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 6.74200 0.01718 392.5 <2e-16 ***

dextrt 1.90328 0.01841 103.4 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for poisson family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 16883.9 on 7 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 831.4 on 6 degrees of freedom

AIC: 911.48

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4Poisson regression: Wald Test

Call:

glm(formula = DUSP1 ~ dex + cell, family = poisson, data = df)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 6.61541 0.02075 318.808 <2e-16 ***

dextrt 1.90328 0.01841 103.363 <2e-16 ***

cellN061011 0.26966 0.01751 15.403 <2e-16 ***

cellN080611 0.21694 0.01771 12.249 <2e-16 ***

cellN61311 -0.01206 0.01870 -0.645 0.519

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for poisson family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 16883.90 on 7 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 416.88 on 3 degrees of freedom

AIC: 502.96

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4Poisson regression: LRT

Analysis of Deviance Table

Model 1: DUSP1 ~ dex

Model 2: DUSP1 ~ dex + cell

Resid. Df Resid. Dev Df Deviance Pr(>Chi)

1 6 831.40

2 3 416.88 3 414.52 < 2.2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1Logistic regression:

Call:

glm(formula = DEATH_EVENT ~ . - time, family = binomial, data = heart)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 4.964e+00 4.601e+00 1.079 0.280625

age 5.569e-02 1.313e-02 4.241 2.23e-05 ***

anaemia 4.179e-01 3.009e-01 1.389 0.164904

creatinine_phosphokinase 2.905e-04 1.428e-04 2.034 0.041907 *

diabetes 1.514e-01 2.974e-01 0.509 0.610644

ejection_fraction -7.032e-02 1.486e-02 -4.731 2.23e-06 ***

high_blood_pressure 4.189e-01 3.061e-01 1.369 0.171092

platelets -7.094e-07 1.617e-06 -0.439 0.660857

serum_creatinine 6.619e-01 1.734e-01 3.817 0.000135 ***

serum_sodium -5.667e-02 3.338e-02 -1.698 0.089558 .

sex -3.990e-01 3.508e-01 -1.137 0.255394

smoking 1.356e-01 3.486e-01 0.389 0.697300

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 375.35 on 298 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 294.28 on 287 degrees of freedom

AIC: 318.28

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 5Logistic regression: Wald test

Analysis of Deviance Table

Model 1: DEATH_EVENT ~ age + sex + smoking

Model 2: DEATH_EVENT ~ (age + anaemia + creatinine_phosphokinase + diabetes +

ejection_fraction + high_blood_pressure + platelets + serum_creatinine +

serum_sodium + sex + smoking + time) - time

Resid. Df Resid. Dev Df Deviance Pr(>Chi)

1 295 355.82

2 287 294.28 8 61.536 2.327e-10 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1